Attractions · Europe · France · Going Out · Regions · Western Europe

3 iconic addresses in Paris

On my previous posts, I mentioned to you some of my “coups de cur” in Paris to give you a few tips on your journey to the capital. Today I would like to talk to you about three iconic addresses in Paris. They might not be of great touristic interest (albeit the “Quai des Orfèvres” is worth-seeing from the outside), yet they are of great historical interest as part of Paris’ DNA. Here is a selection of three, mostly known by their names; let me tell you their stories.

36 quai des Orfèvres: the division of the Police judiciaire headquarters

This is without doubt Paris most iconic address known as the 36″. The building was constructed between 1875 and 1880, based on plans by architects Emile Jacques Gilbert and his son-in-law Arthur-Stanislas Diet. A large part of the Palais de Justice, which previously housed the Parisian Police Prefecture, had been destroyed during a fire started voluntarily during the Paris Commune. Jules Ferry moved the Prefecture to these new premises, supposedly built on the site of a former poultry market. This is, incidentally, what gave the police their traditional nickname poulet (chicken) in French. Another more commonly cited reason is that the term poulet is used to refer to the police because of the presence of a poultry market on the quay alongside the building. The police services moved definitively to the building on 1 August 1913, on the basis of a Decree followed by a Prefectoral Order published by the Prefect Célestin Hennion. The 36, as it is known, was created to put an end to the notorious Bonnot Gang which mocked police from the first motorised vehicles, at a time when police officers remained largely on horseback and bicycle. The building is currently home to three squads: the Crime Squad, the Drug Squad and the Research and Intervention Squads.

Many iconic stories took place within the 36 such as Henri Désiré Landru, Charles Mestorino, Laetitia Toureaux, Mesrine, the gang des postiches(wigs gang), Guy Georges, Françoise Sagan, Mesrine

The 36 is also really important in French popular culture. For example, the famous Inspector Maigret, immortalized by Georges Siménon, is of course the main character of the 36. Inspector Adamsbert, created by Fred Vargas, also climbed the long spiral staircase in the Prefecture, as did Franck Sharko, created by the novelist Frank Thilliez. The cinema has also taken much inspiration from the 36 with, among others, the recebt LAffaire SK1 by Frédéric Tellier starring Nathalie Baye and Raphaël Personnaz, Quai des Orfèvres by Clouzot, 36 Quai des Orfèvres by Olivier Marchand and, to a lesser extent, District 13.

Place Beauvau: the ministry of the interior’s siege

It is actually customary for the French media to refer to the Ministry metonymically as Place Beauvau and to the Minister as the tenant at Place Beauvau. The square owes its name to its proximity to Hôtel Beauvau, a mansion that belonged to the prince and field marshal Charles Juste de Beauvau-Craon (who was born on 10 September 1720, in Lunéville and died on 21 May 1793, in Saint-Germain-en-Laye). Place Beauvau was described in an 1859 publication called LHistoire de Paris as

a chapter, slipped into the text and pages of the aristocratic book that is Rue du Faubourg-Saint-Honoré, of which half is written in English. The district enjoys a well-established popularity with travellers who cross the Channel to compare Paris to London; it is no recent phenomenon that the Paris found beyond Rue Royale is half-filled with foreign features. One remarkable anecdote tells of how one of the very first firefighting pumps was first used to quell a fire that broke out in the Comtesse de Coligarys private mansion on 29 October 1819. The apparatus, designed by Jean-Baptiste Launay, propelled water from Place Beauvau all the way up to the third floor. The squares most impressive building remains, of course, Hôtel Beauvau, which today houses the Ministry of the Interior.

Many iconic stories took place within the 36 such as Henri Désiré Landru, Charles Mestorino, Laetitia Toureaux, Mesrine, the gang des postiches(wigs gang), Guy Georges, Françoise Sagan, Mesrine

The 36 is also really important in French popular culture. For example, the famous Inspector Maigret, immortalized by Georges Siménon, is of course the main character of the 36. Inspector Adamsbert, created by Fred Vargas, also climbed the long spiral staircase in the Prefecture, as did Franck Sharko, created by the novelist Frank Thilliez. The cinema has also taken much inspiration from the 36 with, among others, the recebt LAffaire SK1 by Frédéric Tellier starring Nathalie Baye and Raphaël Personnaz, Quai des Orfèvres by Clouzot, 36 Quai des Orfèvres by Olivier Marchand and, to a lesser extent, District 13.

Place Beauvau: the ministry of the interior’s siege

It is actually customary for the French media to refer to the Ministry metonymically as Place Beauvau and to the Minister as the tenant at Place Beauvau. The square owes its name to its proximity to Hôtel Beauvau, a mansion that belonged to the prince and field marshal Charles Juste de Beauvau-Craon (who was born on 10 September 1720, in Lunéville and died on 21 May 1793, in Saint-Germain-en-Laye). Place Beauvau was described in an 1859 publication called LHistoire de Paris as

a chapter, slipped into the text and pages of the aristocratic book that is Rue du Faubourg-Saint-Honoré, of which half is written in English. The district enjoys a well-established popularity with travellers who cross the Channel to compare Paris to London; it is no recent phenomenon that the Paris found beyond Rue Royale is half-filled with foreign features. One remarkable anecdote tells of how one of the very first firefighting pumps was first used to quell a fire that broke out in the Comtesse de Coligarys private mansion on 29 October 1819. The apparatus, designed by Jean-Baptiste Launay, propelled water from Place Beauvau all the way up to the third floor. The squares most impressive building remains, of course, Hôtel Beauvau, which today houses the Ministry of the Interior.

Armand Gaston Camus (1740-1804), a lawyer in the Parisian parliament, commissioned the building. Architect Nicolas le Camus de Mézières was placed in charge of its construction, and in 1770, the structural works were completed. A Doric peristyle flanked by two entrance wings decorated with arches led the way to the main building, composed of a ground floor and two more square floors above it, with attics at the top. Armand Gaston transferred the lease to Maréchal de Beauvau, Gouverneur de Languedoc, a member of the Académie Française who founded the Beauvau literary circle in 1771. This group was furthered by his nephew, the Chevalier de Boufflers, who lived in the mansion until his death in 1793. Stricken with grief, his widow gave up the lease in 1795, and the property changed hands several times before André, a banker, sold the building to the state in 1859. First of all, it was used to house the temporary Ministry of Algeria; then, in 1861, the Ministry of the Interior finally took up quarters there. Today, the building is rented out on a regular basis as part of a programme to promote government-owned heritage. As a result, the screening of long and short feature films and filming itself often take place in the mansions buildings.

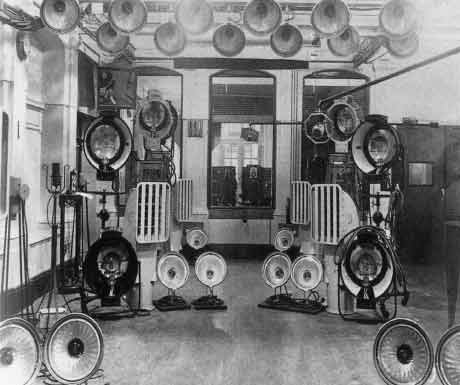

Place Cognacq-Jay: the historic birthplace of French television

When the German occupation began in 1940, the broadcasting studio on Rue de Grenelle, which had been in operation since 1935, was abandoned. The Germans relaunched the Parisian television service in an initiative led by Kurt Hinzmann, a German sent to the French capital in 1941 to develop radio programmes in English in preparation for the day Britain surrendered. He convinced the German authorities to use television as entertainment for injured soldiers (an idea that he had already implemented in Berlin) and, in doing so, find a new use for the Eiffel Tower transmitter, which his managers had asked him to sabotage.

Armand Gaston Camus (1740-1804), a lawyer in the Parisian parliament, commissioned the building. Architect Nicolas le Camus de Mézières was placed in charge of its construction, and in 1770, the structural works were completed. A Doric peristyle flanked by two entrance wings decorated with arches led the way to the main building, composed of a ground floor and two more square floors above it, with attics at the top. Armand Gaston transferred the lease to Maréchal de Beauvau, Gouverneur de Languedoc, a member of the Académie Française who founded the Beauvau literary circle in 1771. This group was furthered by his nephew, the Chevalier de Boufflers, who lived in the mansion until his death in 1793. Stricken with grief, his widow gave up the lease in 1795, and the property changed hands several times before André, a banker, sold the building to the state in 1859. First of all, it was used to house the temporary Ministry of Algeria; then, in 1861, the Ministry of the Interior finally took up quarters there. Today, the building is rented out on a regular basis as part of a programme to promote government-owned heritage. As a result, the screening of long and short feature films and filming itself often take place in the mansions buildings.

Place Cognacq-Jay: the historic birthplace of French television

When the German occupation began in 1940, the broadcasting studio on Rue de Grenelle, which had been in operation since 1935, was abandoned. The Germans relaunched the Parisian television service in an initiative led by Kurt Hinzmann, a German sent to the French capital in 1941 to develop radio programmes in English in preparation for the day Britain surrendered. He convinced the German authorities to use television as entertainment for injured soldiers (an idea that he had already implemented in Berlin) and, in doing so, find a new use for the Eiffel Tower transmitter, which his managers had asked him to sabotage.

In 1943, around 300 German-made television sets were distributed to hospitals around Paris, as well as to a handful of officers. A studio was set up at 15 Avenue Charles Floquet, in the former Embassy of Czechoslovakia and not far from the Eiffel Tower, until larger premises became available.

Then Hinzmann found a disused dancehall at 180 Rue de lUniversité. The hall was large enough to be converted into a studio. Behind it, there was an abandoned garage which could be used as a workshop, and this in turn was attached to a nice building a boarding house whose street address was 13-15 Rue Cognacq-Jay which could be used for administrative offices. The arrangement was perfect, especially since the Eiffel Tower was just down the road. The buildings were requisitioned immediately and the owner unceremoniously dispossessed of his property. From then on, the premises were devoted to French broadcasting. On 7 May 1943, the first programmes were aired. The German channel Fernsehsender Paris broadcast programmes from this address until 12 August 1944.

When the Germans finally fled the studios, they left France a television station that was not only fully operational, but also one of the finest in the world. In 1945, Jean Guignebert, the director of Radiodiffusion Nationale, decided that the building in which Fernsehsender Paris had been run should be renamed the Centre Alfred Lelluch. Broadcasting returned to normal in October 1945. At the time, only 1% of French households had their own television set.

After the war: back to you, Cognacq-Jay

After the war, the studios became the home of the rebirth of French television and were used from the Liberation right up until 1992, when leading channel TF1 moved to Boulogne. Although it was originally designed to host a single television channel, the Centre Alfred Lelluch also housed the studios and controls of the countrys second channel from December 1963, and of its third from December 1972.

The three channels shared the studios until 1994, even though Antenne 2 and France Régions 3 had had their own headquarters since 1975. Global French-language network TV5 established its head office there in 1984 and took up two and a half floors. After being privatised in April 1987, TF1 remained in the premises whilst its new head office was being built in Boulogne-Billancourt, where it moved in May 1992. In 1994, France 2 and France 3s master control left Cognacq-Jay for Rue Varet in the 15th arrondissement of Paris. TV5 Monde left the iconic address at the end of July 2006, leaving behind only cable, satellite and TNT channels, which shared Cognacq-Jays sets, cameras and control rooms. Today, the property still belongs to TDF, Frances largest transmissions company.French televisions biggest voices, including Léon Zitrone and Guy Lux, immortalised the iconic address with a saying that has become renowned: A vous Cognacq-Jay (Back to you, Cognacq-Jay) were the words with which reporters handed back to news anchors. In 2010, Editions Delcourt published A vous Cognacq-Jay, a comic book dedicated to the glory days of French television in the 60s and 70s.

Didier Moinel Delalande is a Director at Hotel Mathurin.

If you would like to be a guest blogger on A Luxury Travel Blog in order to raise your profile, please contact us.

In 1943, around 300 German-made television sets were distributed to hospitals around Paris, as well as to a handful of officers. A studio was set up at 15 Avenue Charles Floquet, in the former Embassy of Czechoslovakia and not far from the Eiffel Tower, until larger premises became available.

Then Hinzmann found a disused dancehall at 180 Rue de lUniversité. The hall was large enough to be converted into a studio. Behind it, there was an abandoned garage which could be used as a workshop, and this in turn was attached to a nice building a boarding house whose street address was 13-15 Rue Cognacq-Jay which could be used for administrative offices. The arrangement was perfect, especially since the Eiffel Tower was just down the road. The buildings were requisitioned immediately and the owner unceremoniously dispossessed of his property. From then on, the premises were devoted to French broadcasting. On 7 May 1943, the first programmes were aired. The German channel Fernsehsender Paris broadcast programmes from this address until 12 August 1944.

When the Germans finally fled the studios, they left France a television station that was not only fully operational, but also one of the finest in the world. In 1945, Jean Guignebert, the director of Radiodiffusion Nationale, decided that the building in which Fernsehsender Paris had been run should be renamed the Centre Alfred Lelluch. Broadcasting returned to normal in October 1945. At the time, only 1% of French households had their own television set.

After the war: back to you, Cognacq-Jay

After the war, the studios became the home of the rebirth of French television and were used from the Liberation right up until 1992, when leading channel TF1 moved to Boulogne. Although it was originally designed to host a single television channel, the Centre Alfred Lelluch also housed the studios and controls of the countrys second channel from December 1963, and of its third from December 1972.

The three channels shared the studios until 1994, even though Antenne 2 and France Régions 3 had had their own headquarters since 1975. Global French-language network TV5 established its head office there in 1984 and took up two and a half floors. After being privatised in April 1987, TF1 remained in the premises whilst its new head office was being built in Boulogne-Billancourt, where it moved in May 1992. In 1994, France 2 and France 3s master control left Cognacq-Jay for Rue Varet in the 15th arrondissement of Paris. TV5 Monde left the iconic address at the end of July 2006, leaving behind only cable, satellite and TNT channels, which shared Cognacq-Jays sets, cameras and control rooms. Today, the property still belongs to TDF, Frances largest transmissions company.French televisions biggest voices, including Léon Zitrone and Guy Lux, immortalised the iconic address with a saying that has become renowned: A vous Cognacq-Jay (Back to you, Cognacq-Jay) were the words with which reporters handed back to news anchors. In 2010, Editions Delcourt published A vous Cognacq-Jay, a comic book dedicated to the glory days of French television in the 60s and 70s.

Didier Moinel Delalande is a Director at Hotel Mathurin.

If you would like to be a guest blogger on A Luxury Travel Blog in order to raise your profile, please contact us.

Many iconic stories took place within the 36 such as Henri Désiré Landru, Charles Mestorino, Laetitia Toureaux, Mesrine, the gang des postiches(wigs gang), Guy Georges, Françoise Sagan, Mesrine

The 36 is also really important in French popular culture. For example, the famous Inspector Maigret, immortalized by Georges Siménon, is of course the main character of the 36. Inspector Adamsbert, created by Fred Vargas, also climbed the long spiral staircase in the Prefecture, as did Franck Sharko, created by the novelist Frank Thilliez. The cinema has also taken much inspiration from the 36 with, among others, the recebt LAffaire SK1 by Frédéric Tellier starring Nathalie Baye and Raphaël Personnaz, Quai des Orfèvres by Clouzot, 36 Quai des Orfèvres by Olivier Marchand and, to a lesser extent, District 13.

Place Beauvau: the ministry of the interior’s siege

It is actually customary for the French media to refer to the Ministry metonymically as Place Beauvau and to the Minister as the tenant at Place Beauvau. The square owes its name to its proximity to Hôtel Beauvau, a mansion that belonged to the prince and field marshal Charles Juste de Beauvau-Craon (who was born on 10 September 1720, in Lunéville and died on 21 May 1793, in Saint-Germain-en-Laye). Place Beauvau was described in an 1859 publication called LHistoire de Paris as

a chapter, slipped into the text and pages of the aristocratic book that is Rue du Faubourg-Saint-Honoré, of which half is written in English. The district enjoys a well-established popularity with travellers who cross the Channel to compare Paris to London; it is no recent phenomenon that the Paris found beyond Rue Royale is half-filled with foreign features. One remarkable anecdote tells of how one of the very first firefighting pumps was first used to quell a fire that broke out in the Comtesse de Coligarys private mansion on 29 October 1819. The apparatus, designed by Jean-Baptiste Launay, propelled water from Place Beauvau all the way up to the third floor. The squares most impressive building remains, of course, Hôtel Beauvau, which today houses the Ministry of the Interior.

Many iconic stories took place within the 36 such as Henri Désiré Landru, Charles Mestorino, Laetitia Toureaux, Mesrine, the gang des postiches(wigs gang), Guy Georges, Françoise Sagan, Mesrine

The 36 is also really important in French popular culture. For example, the famous Inspector Maigret, immortalized by Georges Siménon, is of course the main character of the 36. Inspector Adamsbert, created by Fred Vargas, also climbed the long spiral staircase in the Prefecture, as did Franck Sharko, created by the novelist Frank Thilliez. The cinema has also taken much inspiration from the 36 with, among others, the recebt LAffaire SK1 by Frédéric Tellier starring Nathalie Baye and Raphaël Personnaz, Quai des Orfèvres by Clouzot, 36 Quai des Orfèvres by Olivier Marchand and, to a lesser extent, District 13.

Place Beauvau: the ministry of the interior’s siege

It is actually customary for the French media to refer to the Ministry metonymically as Place Beauvau and to the Minister as the tenant at Place Beauvau. The square owes its name to its proximity to Hôtel Beauvau, a mansion that belonged to the prince and field marshal Charles Juste de Beauvau-Craon (who was born on 10 September 1720, in Lunéville and died on 21 May 1793, in Saint-Germain-en-Laye). Place Beauvau was described in an 1859 publication called LHistoire de Paris as

a chapter, slipped into the text and pages of the aristocratic book that is Rue du Faubourg-Saint-Honoré, of which half is written in English. The district enjoys a well-established popularity with travellers who cross the Channel to compare Paris to London; it is no recent phenomenon that the Paris found beyond Rue Royale is half-filled with foreign features. One remarkable anecdote tells of how one of the very first firefighting pumps was first used to quell a fire that broke out in the Comtesse de Coligarys private mansion on 29 October 1819. The apparatus, designed by Jean-Baptiste Launay, propelled water from Place Beauvau all the way up to the third floor. The squares most impressive building remains, of course, Hôtel Beauvau, which today houses the Ministry of the Interior.

Armand Gaston Camus (1740-1804), a lawyer in the Parisian parliament, commissioned the building. Architect Nicolas le Camus de Mézières was placed in charge of its construction, and in 1770, the structural works were completed. A Doric peristyle flanked by two entrance wings decorated with arches led the way to the main building, composed of a ground floor and two more square floors above it, with attics at the top. Armand Gaston transferred the lease to Maréchal de Beauvau, Gouverneur de Languedoc, a member of the Académie Française who founded the Beauvau literary circle in 1771. This group was furthered by his nephew, the Chevalier de Boufflers, who lived in the mansion until his death in 1793. Stricken with grief, his widow gave up the lease in 1795, and the property changed hands several times before André, a banker, sold the building to the state in 1859. First of all, it was used to house the temporary Ministry of Algeria; then, in 1861, the Ministry of the Interior finally took up quarters there. Today, the building is rented out on a regular basis as part of a programme to promote government-owned heritage. As a result, the screening of long and short feature films and filming itself often take place in the mansions buildings.

Place Cognacq-Jay: the historic birthplace of French television

When the German occupation began in 1940, the broadcasting studio on Rue de Grenelle, which had been in operation since 1935, was abandoned. The Germans relaunched the Parisian television service in an initiative led by Kurt Hinzmann, a German sent to the French capital in 1941 to develop radio programmes in English in preparation for the day Britain surrendered. He convinced the German authorities to use television as entertainment for injured soldiers (an idea that he had already implemented in Berlin) and, in doing so, find a new use for the Eiffel Tower transmitter, which his managers had asked him to sabotage.

Armand Gaston Camus (1740-1804), a lawyer in the Parisian parliament, commissioned the building. Architect Nicolas le Camus de Mézières was placed in charge of its construction, and in 1770, the structural works were completed. A Doric peristyle flanked by two entrance wings decorated with arches led the way to the main building, composed of a ground floor and two more square floors above it, with attics at the top. Armand Gaston transferred the lease to Maréchal de Beauvau, Gouverneur de Languedoc, a member of the Académie Française who founded the Beauvau literary circle in 1771. This group was furthered by his nephew, the Chevalier de Boufflers, who lived in the mansion until his death in 1793. Stricken with grief, his widow gave up the lease in 1795, and the property changed hands several times before André, a banker, sold the building to the state in 1859. First of all, it was used to house the temporary Ministry of Algeria; then, in 1861, the Ministry of the Interior finally took up quarters there. Today, the building is rented out on a regular basis as part of a programme to promote government-owned heritage. As a result, the screening of long and short feature films and filming itself often take place in the mansions buildings.

Place Cognacq-Jay: the historic birthplace of French television

When the German occupation began in 1940, the broadcasting studio on Rue de Grenelle, which had been in operation since 1935, was abandoned. The Germans relaunched the Parisian television service in an initiative led by Kurt Hinzmann, a German sent to the French capital in 1941 to develop radio programmes in English in preparation for the day Britain surrendered. He convinced the German authorities to use television as entertainment for injured soldiers (an idea that he had already implemented in Berlin) and, in doing so, find a new use for the Eiffel Tower transmitter, which his managers had asked him to sabotage.

In 1943, around 300 German-made television sets were distributed to hospitals around Paris, as well as to a handful of officers. A studio was set up at 15 Avenue Charles Floquet, in the former Embassy of Czechoslovakia and not far from the Eiffel Tower, until larger premises became available.

Then Hinzmann found a disused dancehall at 180 Rue de lUniversité. The hall was large enough to be converted into a studio. Behind it, there was an abandoned garage which could be used as a workshop, and this in turn was attached to a nice building a boarding house whose street address was 13-15 Rue Cognacq-Jay which could be used for administrative offices. The arrangement was perfect, especially since the Eiffel Tower was just down the road. The buildings were requisitioned immediately and the owner unceremoniously dispossessed of his property. From then on, the premises were devoted to French broadcasting. On 7 May 1943, the first programmes were aired. The German channel Fernsehsender Paris broadcast programmes from this address until 12 August 1944.

When the Germans finally fled the studios, they left France a television station that was not only fully operational, but also one of the finest in the world. In 1945, Jean Guignebert, the director of Radiodiffusion Nationale, decided that the building in which Fernsehsender Paris had been run should be renamed the Centre Alfred Lelluch. Broadcasting returned to normal in October 1945. At the time, only 1% of French households had their own television set.

After the war: back to you, Cognacq-Jay

After the war, the studios became the home of the rebirth of French television and were used from the Liberation right up until 1992, when leading channel TF1 moved to Boulogne. Although it was originally designed to host a single television channel, the Centre Alfred Lelluch also housed the studios and controls of the countrys second channel from December 1963, and of its third from December 1972.

The three channels shared the studios until 1994, even though Antenne 2 and France Régions 3 had had their own headquarters since 1975. Global French-language network TV5 established its head office there in 1984 and took up two and a half floors. After being privatised in April 1987, TF1 remained in the premises whilst its new head office was being built in Boulogne-Billancourt, where it moved in May 1992. In 1994, France 2 and France 3s master control left Cognacq-Jay for Rue Varet in the 15th arrondissement of Paris. TV5 Monde left the iconic address at the end of July 2006, leaving behind only cable, satellite and TNT channels, which shared Cognacq-Jays sets, cameras and control rooms. Today, the property still belongs to TDF, Frances largest transmissions company.French televisions biggest voices, including Léon Zitrone and Guy Lux, immortalised the iconic address with a saying that has become renowned: A vous Cognacq-Jay (Back to you, Cognacq-Jay) were the words with which reporters handed back to news anchors. In 2010, Editions Delcourt published A vous Cognacq-Jay, a comic book dedicated to the glory days of French television in the 60s and 70s.

Didier Moinel Delalande is a Director at Hotel Mathurin.

If you would like to be a guest blogger on A Luxury Travel Blog in order to raise your profile, please contact us.

In 1943, around 300 German-made television sets were distributed to hospitals around Paris, as well as to a handful of officers. A studio was set up at 15 Avenue Charles Floquet, in the former Embassy of Czechoslovakia and not far from the Eiffel Tower, until larger premises became available.

Then Hinzmann found a disused dancehall at 180 Rue de lUniversité. The hall was large enough to be converted into a studio. Behind it, there was an abandoned garage which could be used as a workshop, and this in turn was attached to a nice building a boarding house whose street address was 13-15 Rue Cognacq-Jay which could be used for administrative offices. The arrangement was perfect, especially since the Eiffel Tower was just down the road. The buildings were requisitioned immediately and the owner unceremoniously dispossessed of his property. From then on, the premises were devoted to French broadcasting. On 7 May 1943, the first programmes were aired. The German channel Fernsehsender Paris broadcast programmes from this address until 12 August 1944.

When the Germans finally fled the studios, they left France a television station that was not only fully operational, but also one of the finest in the world. In 1945, Jean Guignebert, the director of Radiodiffusion Nationale, decided that the building in which Fernsehsender Paris had been run should be renamed the Centre Alfred Lelluch. Broadcasting returned to normal in October 1945. At the time, only 1% of French households had their own television set.

After the war: back to you, Cognacq-Jay

After the war, the studios became the home of the rebirth of French television and were used from the Liberation right up until 1992, when leading channel TF1 moved to Boulogne. Although it was originally designed to host a single television channel, the Centre Alfred Lelluch also housed the studios and controls of the countrys second channel from December 1963, and of its third from December 1972.

The three channels shared the studios until 1994, even though Antenne 2 and France Régions 3 had had their own headquarters since 1975. Global French-language network TV5 established its head office there in 1984 and took up two and a half floors. After being privatised in April 1987, TF1 remained in the premises whilst its new head office was being built in Boulogne-Billancourt, where it moved in May 1992. In 1994, France 2 and France 3s master control left Cognacq-Jay for Rue Varet in the 15th arrondissement of Paris. TV5 Monde left the iconic address at the end of July 2006, leaving behind only cable, satellite and TNT channels, which shared Cognacq-Jays sets, cameras and control rooms. Today, the property still belongs to TDF, Frances largest transmissions company.French televisions biggest voices, including Léon Zitrone and Guy Lux, immortalised the iconic address with a saying that has become renowned: A vous Cognacq-Jay (Back to you, Cognacq-Jay) were the words with which reporters handed back to news anchors. In 2010, Editions Delcourt published A vous Cognacq-Jay, a comic book dedicated to the glory days of French television in the 60s and 70s.

Didier Moinel Delalande is a Director at Hotel Mathurin.

If you would like to be a guest blogger on A Luxury Travel Blog in order to raise your profile, please contact us.Did you enjoy this article?

Receive similar content direct to your inbox.

Happily, Paris is a beauty in every season!

36 Quai d’Orvèvres: huge police scandal is going on right right now inside.

Yes, corruption & cocaine are involved – among a bag of money at the ground of a lake.

Sounds like a movie. But sometimes reality is absurd enough.