Asia · Attractions · Cambodia · Going Out · Regions

Why you should visit Phnom Penh prison and killing fields

We travelled the world visiting 15 countries in 10 months but nothing could have prepared us for the horror we found during our visits to the security prison and the killings fields, that day in Phnom Penh.

Pol Pot established Kampuchea, the Khmer Rouge controlled state, and took over the Tuol Svay Prey High School in the capital of Cambodia, Phnom Penh. He transformed it into Tuol Sleng the notorious security prison called S.21 a torture and interrogation centre run by the Khmer Rouge.

My first impression was surprise that this torture centre, or Genocide Museum as it is now known, was right in the middle of the city. It looks like any other high school; five three storey buildings, about the size of a UK junior school, face on to a play area with gym apparatus, courtyard and green lawns. We were to find out later that this play area and apparatus was adapted to torture prisoners.

Surprisingly, it is not in ruins, far from it, it is in near perfect condition having been built in 1962. But then we forget it was converted to a torture centre only 40 years ago, in the mid 1970’s.

20,000 prisoners at Tuol Sleng were tortured, interrogated and “processed” before transportation to the killing fields, seven survived. Seven survived, out of twenty thousand.

Our guide was Socmail a quietly spoken lady in her mid fifties. As she led our small party into the classrooms converted to torture chambers she recounted how the monks, artists, professionals, doctors, teachers, the educated and intellectuals were all arrested on suspicion of being traitors to the new state. Bizarrely this included anyone with glasses or soft hands and those who could speak a foreign language.

The decaying 15 ft square rooms, had the original rusting beds in place with their chains and shackles attached, alongside the instruments of torture. Every inmate was interrogated each day until they confessed to something, anything to stop the pain.

The rooms would have included a typewriter so when the prisoner admitted to an act of treason the interrogator would stop the punishment and record the confession. Once completed it was given to the victim for an X to be scrawled onto the paper. They had in effect signed their own death warrant, the Khmer Rouge believed they now had the justification to send the prisoner to the killing fields.

My first impression was surprise that this torture centre, or Genocide Museum as it is now known, was right in the middle of the city. It looks like any other high school; five three storey buildings, about the size of a UK junior school, face on to a play area with gym apparatus, courtyard and green lawns. We were to find out later that this play area and apparatus was adapted to torture prisoners.

Surprisingly, it is not in ruins, far from it, it is in near perfect condition having been built in 1962. But then we forget it was converted to a torture centre only 40 years ago, in the mid 1970’s.

20,000 prisoners at Tuol Sleng were tortured, interrogated and “processed” before transportation to the killing fields, seven survived. Seven survived, out of twenty thousand.

Our guide was Socmail a quietly spoken lady in her mid fifties. As she led our small party into the classrooms converted to torture chambers she recounted how the monks, artists, professionals, doctors, teachers, the educated and intellectuals were all arrested on suspicion of being traitors to the new state. Bizarrely this included anyone with glasses or soft hands and those who could speak a foreign language.

The decaying 15 ft square rooms, had the original rusting beds in place with their chains and shackles attached, alongside the instruments of torture. Every inmate was interrogated each day until they confessed to something, anything to stop the pain.

The rooms would have included a typewriter so when the prisoner admitted to an act of treason the interrogator would stop the punishment and record the confession. Once completed it was given to the victim for an X to be scrawled onto the paper. They had in effect signed their own death warrant, the Khmer Rouge believed they now had the justification to send the prisoner to the killing fields.

Unbelievably brutal and barbaric torture at Tuol Sleng included electric shock, water boarding with boiling water, nail extraction with alcohol poured over the wounds, drowning, hanging and scorpion stings for the women. This was torture on an industrial scale, vicious, inhumane and excessively cruel.

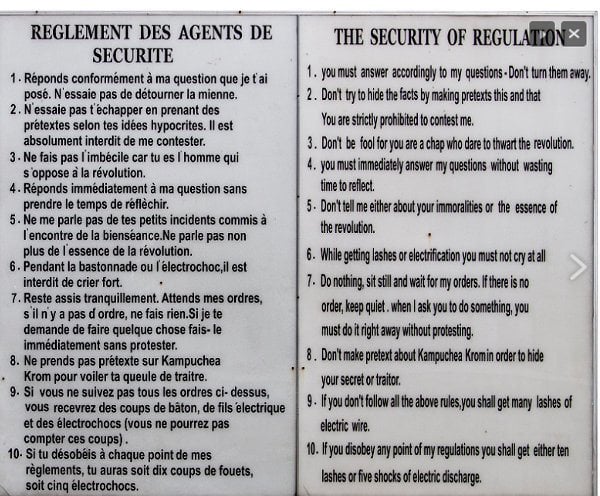

The Security of Regulation sign remains in the school courtyard, new inmates were forced to recite it when they arrived.

Unbelievably brutal and barbaric torture at Tuol Sleng included electric shock, water boarding with boiling water, nail extraction with alcohol poured over the wounds, drowning, hanging and scorpion stings for the women. This was torture on an industrial scale, vicious, inhumane and excessively cruel.

The Security of Regulation sign remains in the school courtyard, new inmates were forced to recite it when they arrived.

Each inmate was photographed on arrival and if they died during torture they were photographed again so the image could be sent to the Khmer Rouge officials.

It was during this explanation that Socmail quietly told us that her brother and her father, a teacher, had both been taken to Tuol Sleng, never to return. Our little group fell silent, what can you say?

At the age of 13 she was expelled from Phnom Penh and forced to walk the 183 miles to Bat Tambang to work in the rice fields for the Kampuchea Democratic Regime, it took three months. Socmail said she worked 12 hours a day for three years, eight months and twenty days, that was forty three years ago, she had counted each day there.

We were shown classrooms on the second floor where up to 50 prisoners were shackled together to sleep on the hard stone floors. The rusted rods and manacles were piled in a corner and the steel hooks in the floor were still in place. Greying black and white photos on the walls showed what was found in the torture rooms when Phnom Phen was liberated; 14 tortured bodies bloodied, bare and broken were left on their beds.

Further rooms were lined with thousands of mug shots of prisoners, some alive some dead, all were tortured. Barbed wire was still strung across the exterior landings to prevent suicide, death was a better alternative than life in the prison. The tour was remorseless in its brutal reality.

Each inmate was photographed on arrival and if they died during torture they were photographed again so the image could be sent to the Khmer Rouge officials.

It was during this explanation that Socmail quietly told us that her brother and her father, a teacher, had both been taken to Tuol Sleng, never to return. Our little group fell silent, what can you say?

At the age of 13 she was expelled from Phnom Penh and forced to walk the 183 miles to Bat Tambang to work in the rice fields for the Kampuchea Democratic Regime, it took three months. Socmail said she worked 12 hours a day for three years, eight months and twenty days, that was forty three years ago, she had counted each day there.

We were shown classrooms on the second floor where up to 50 prisoners were shackled together to sleep on the hard stone floors. The rusted rods and manacles were piled in a corner and the steel hooks in the floor were still in place. Greying black and white photos on the walls showed what was found in the torture rooms when Phnom Phen was liberated; 14 tortured bodies bloodied, bare and broken were left on their beds.

Further rooms were lined with thousands of mug shots of prisoners, some alive some dead, all were tortured. Barbed wire was still strung across the exterior landings to prevent suicide, death was a better alternative than life in the prison. The tour was remorseless in its brutal reality.

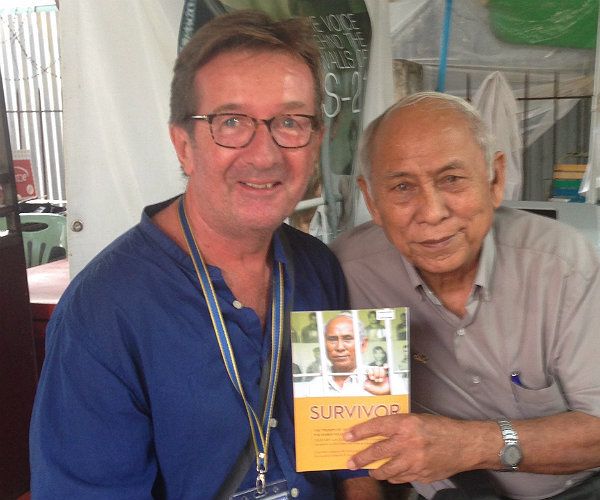

Of the seven survivors, two are still alive today, one of them is Chum Mey. We visited his cell, number 022, a clumsily built brick space of about six feet in length and no more than three feet wide, his chains, shackles and latrine box remain. He survived gunfights with the Khmer Rouge, rocket attacks during the civil war and having been dragged blindfolded to Tuol Sleng, endured 12 days and nights of repeated beatings, torture and electrocution. He lost his wife and four children during the brutal Khmer Rouge regime and saw friends and family chained, tortured and processed in the assembly line of death.

He confessed to counter revolutionary work for the CIA, an organisation he had never heard of before the torture began, but anything to stop the pain. He was a mechanic by trade and his life was spared when he offered to fix his own interrogators’ typewriter. He was given food and put to work mending all the prison typewriters until the liberation troops arrived.

I asked Socmail about his life after the liberation in 1979.

‘You can ask him yourself,’ she said, ‘he’s visiting today, would you like to meet him?’ This took me completely by surprise, but what an honour, what a rare privilege.

Chum Mey is now a charming, cheerful and contented 86 year old. Perhaps surprisingly, he is happy to talk about his time in Tuol Sleng, maybe it’s part of the healing process, but his physical scars are still apparent.

Of the seven survivors, two are still alive today, one of them is Chum Mey. We visited his cell, number 022, a clumsily built brick space of about six feet in length and no more than three feet wide, his chains, shackles and latrine box remain. He survived gunfights with the Khmer Rouge, rocket attacks during the civil war and having been dragged blindfolded to Tuol Sleng, endured 12 days and nights of repeated beatings, torture and electrocution. He lost his wife and four children during the brutal Khmer Rouge regime and saw friends and family chained, tortured and processed in the assembly line of death.

He confessed to counter revolutionary work for the CIA, an organisation he had never heard of before the torture began, but anything to stop the pain. He was a mechanic by trade and his life was spared when he offered to fix his own interrogators’ typewriter. He was given food and put to work mending all the prison typewriters until the liberation troops arrived.

I asked Socmail about his life after the liberation in 1979.

‘You can ask him yourself,’ she said, ‘he’s visiting today, would you like to meet him?’ This took me completely by surprise, but what an honour, what a rare privilege.

Chum Mey is now a charming, cheerful and contented 86 year old. Perhaps surprisingly, he is happy to talk about his time in Tuol Sleng, maybe it’s part of the healing process, but his physical scars are still apparent.

We met for a few minutes, I have to say I was overwhelmed by this guy. I had just heard his tragic story and stood where he was tortured yet he greeted me like an old friend. The lump in my throat made my voice falter and tears stung my eyes as he took my hand and posed for a photograph, he was far more in control than me. How do you react in such circumstances? Frown, glare, grimace? I turned to him to see a broad smile and genuine happiness on his face. How my wife Helene managed to take the shot with tears streaming down her face I don’t know but that picture and the signed book I have from him are extremely special and treasured souvenirs from our amazing 10 month adventure.

We talked for a few minutes through an interpreter about his time spent 40 years ago in the very place he was now visiting as a guest. He was keen to explain the torture and showed me his broken bent fingers where he tried to defend himself from the clubbing he received all those years ago, and the deformed toes where his nails had been viciously pulled from their sockets with pliers. His body may not have healed but his mind was alert and quick, answering my questions explicitly and with clarity.

‘Why are you here today?’ I asked, ‘surely you would prefer to forget the past and lead your own life without being reminded of the atrocities you experienced?’

‘No, David,’ he was quick to correct me. ‘I am one of a handful to survive and most of them are now gone. I believe it is my duty to tell my story, I want the world to know what really happened. I don’t want those thousands who died horrible deaths to be forgotten. Then perhaps we won’t see this terrible time repeated again, not just here, but anywhere in the world.’

What a courageous man.

While Pol Pot’s utopian vision was becoming a reality his cleansing programme grew to staggering levels. When an interrogation extracted a name, the whole family would be arrested and sent to Tuol Sleng and wiped out at the killing fields. This was our next visit.

Choeung Ek is about 10 miles southeast of the city in the lush landscape of rural Cambodia, it is also the most well known of the 300 killing fields found all over the country. It is here that the inmates from Tuol Sleng were transported in their thousands for execution.

We met for a few minutes, I have to say I was overwhelmed by this guy. I had just heard his tragic story and stood where he was tortured yet he greeted me like an old friend. The lump in my throat made my voice falter and tears stung my eyes as he took my hand and posed for a photograph, he was far more in control than me. How do you react in such circumstances? Frown, glare, grimace? I turned to him to see a broad smile and genuine happiness on his face. How my wife Helene managed to take the shot with tears streaming down her face I don’t know but that picture and the signed book I have from him are extremely special and treasured souvenirs from our amazing 10 month adventure.

We talked for a few minutes through an interpreter about his time spent 40 years ago in the very place he was now visiting as a guest. He was keen to explain the torture and showed me his broken bent fingers where he tried to defend himself from the clubbing he received all those years ago, and the deformed toes where his nails had been viciously pulled from their sockets with pliers. His body may not have healed but his mind was alert and quick, answering my questions explicitly and with clarity.

‘Why are you here today?’ I asked, ‘surely you would prefer to forget the past and lead your own life without being reminded of the atrocities you experienced?’

‘No, David,’ he was quick to correct me. ‘I am one of a handful to survive and most of them are now gone. I believe it is my duty to tell my story, I want the world to know what really happened. I don’t want those thousands who died horrible deaths to be forgotten. Then perhaps we won’t see this terrible time repeated again, not just here, but anywhere in the world.’

What a courageous man.

While Pol Pot’s utopian vision was becoming a reality his cleansing programme grew to staggering levels. When an interrogation extracted a name, the whole family would be arrested and sent to Tuol Sleng and wiped out at the killing fields. This was our next visit.

Choeung Ek is about 10 miles southeast of the city in the lush landscape of rural Cambodia, it is also the most well known of the 300 killing fields found all over the country. It is here that the inmates from Tuol Sleng were transported in their thousands for execution.

Between 1976 and ’78 Tuol Sleng would send up to 300 people a day to Choeung Ek. Tortured, terrified and traumatised victims the Khmer Rouge believed had committed crimes against the state. Trucks loaded with men, women, children and babies to be slaughtered the night they arrived.

The area has hardly been touched since the end of the Khmer Rouge regime in 1979. Although there are paths and some boardwalks over the 129 mass grave pits, when it rains there is still the faint odour of rotting corpses, while bones, teeth and pieces of clothing rise to the surface.

Each visitor is provided with headphones and an audio commentary so the memorial site is eerily quiet as groups and couples split up for each individual to try and understand this astonishingly sad environment at their own pace. There are visitors in silent contemplation sitting under trees, others unashamedly sobbing as the narrative plays out and some clearly unable to take in what they are seeing and hearing. It is tough.

Likewise, Helene and I separated rather than share the experience, I think one has to manage this in one’s own way.

Victims were told they were being taken to a safer environment but were blindfolded and murdered on the side of the mass graves in the most efficient, expedient and inexpensive way possible. Few bullets were used, they were too costly, so they were hacked and bludgeoned to death with what they called “killing tools”, nothing more than farm implements. Scythes, axes, bayonets, cleaning rods, chisels, knives, hammers and clubs were displayed alongside the skulls that they had beaten and broken.

One mass grave of about 15 x 30 feet contained 450 victims, another 166 without heads. The Magic Tree was in the centre of the mass graves, it was used to hang speakers playing loud music during the executions to drown out the screams of the dying. The brutality here was almost palpable.

The most harrowing by far was The Killing Tree alongside a 12 x 12 foot mass grave of 100 naked women, young children and babies. Unbelievably, the bullets were reserved for the babies, not out of any sense of morality, compassion or sympathy but grotesquely for fun. One executioner would throw the baby in the air for another to shoot at it.

The obscenity of the executioner’s actions continued with The Killing Tree, it has a large well established trunk perhaps a metre in its diameter, it is covered with thousands of donated colourful wristbands, beside it is a distressing hand painted sign.

Between 1976 and ’78 Tuol Sleng would send up to 300 people a day to Choeung Ek. Tortured, terrified and traumatised victims the Khmer Rouge believed had committed crimes against the state. Trucks loaded with men, women, children and babies to be slaughtered the night they arrived.

The area has hardly been touched since the end of the Khmer Rouge regime in 1979. Although there are paths and some boardwalks over the 129 mass grave pits, when it rains there is still the faint odour of rotting corpses, while bones, teeth and pieces of clothing rise to the surface.

Each visitor is provided with headphones and an audio commentary so the memorial site is eerily quiet as groups and couples split up for each individual to try and understand this astonishingly sad environment at their own pace. There are visitors in silent contemplation sitting under trees, others unashamedly sobbing as the narrative plays out and some clearly unable to take in what they are seeing and hearing. It is tough.

Likewise, Helene and I separated rather than share the experience, I think one has to manage this in one’s own way.

Victims were told they were being taken to a safer environment but were blindfolded and murdered on the side of the mass graves in the most efficient, expedient and inexpensive way possible. Few bullets were used, they were too costly, so they were hacked and bludgeoned to death with what they called “killing tools”, nothing more than farm implements. Scythes, axes, bayonets, cleaning rods, chisels, knives, hammers and clubs were displayed alongside the skulls that they had beaten and broken.

One mass grave of about 15 x 30 feet contained 450 victims, another 166 without heads. The Magic Tree was in the centre of the mass graves, it was used to hang speakers playing loud music during the executions to drown out the screams of the dying. The brutality here was almost palpable.

The most harrowing by far was The Killing Tree alongside a 12 x 12 foot mass grave of 100 naked women, young children and babies. Unbelievably, the bullets were reserved for the babies, not out of any sense of morality, compassion or sympathy but grotesquely for fun. One executioner would throw the baby in the air for another to shoot at it.

The obscenity of the executioner’s actions continued with The Killing Tree, it has a large well established trunk perhaps a metre in its diameter, it is covered with thousands of donated colourful wristbands, beside it is a distressing hand painted sign.

A 62 metre tall Memorial Stupa was built in 1988. It is a Buddhist construction of 17 shallow levels with acrylic sides, the first ten of which displays 9,000 skulls. The remaining levels carry some of the victim’s bones but there was just not enough space to display them all so most are left in the earth.

A 62 metre tall Memorial Stupa was built in 1988. It is a Buddhist construction of 17 shallow levels with acrylic sides, the first ten of which displays 9,000 skulls. The remaining levels carry some of the victim’s bones but there was just not enough space to display them all so most are left in the earth.

The day’s experience was of course shocking and distressing, I believe we were both somewhat traumatised by what we encountered.

As we left the Killing field of Choeung Ek the audio narrative finished with a poignant message. “What happened here was tragic but not unique. It’s happened across the globe in the past, and may well happen again. It is a lesson we must all learn from, so as you return home remember our past when you look towards your future.”

It was a powerful message, echoing the conversation I had earlier in the day with the brave Chum Mey. In my book of our 10 month adventure I was tempted not to describe what I saw and heard. But my conversation with Chum Mey and the final audio message persuaded me otherwise. Perhaps we too have a duty to tell the story of what really happened, this is why I believe you should visit Phnom Penh prison and the killing fields.

David Moore is Author of ‘Turning Left Around the World’. Published by Mirador and available from Amazon, it is an entertaining account of David and his wife’s travel adventures – often intriguing, frequently funny and occasionally tragic.

If you would like to be a guest blogger on A Luxury Travel Blog in order to raise your profile, please contact us.

The day’s experience was of course shocking and distressing, I believe we were both somewhat traumatised by what we encountered.

As we left the Killing field of Choeung Ek the audio narrative finished with a poignant message. “What happened here was tragic but not unique. It’s happened across the globe in the past, and may well happen again. It is a lesson we must all learn from, so as you return home remember our past when you look towards your future.”

It was a powerful message, echoing the conversation I had earlier in the day with the brave Chum Mey. In my book of our 10 month adventure I was tempted not to describe what I saw and heard. But my conversation with Chum Mey and the final audio message persuaded me otherwise. Perhaps we too have a duty to tell the story of what really happened, this is why I believe you should visit Phnom Penh prison and the killing fields.

David Moore is Author of ‘Turning Left Around the World’. Published by Mirador and available from Amazon, it is an entertaining account of David and his wife’s travel adventures – often intriguing, frequently funny and occasionally tragic.

If you would like to be a guest blogger on A Luxury Travel Blog in order to raise your profile, please contact us.

My first impression was surprise that this torture centre, or Genocide Museum as it is now known, was right in the middle of the city. It looks like any other high school; five three storey buildings, about the size of a UK junior school, face on to a play area with gym apparatus, courtyard and green lawns. We were to find out later that this play area and apparatus was adapted to torture prisoners.

Surprisingly, it is not in ruins, far from it, it is in near perfect condition having been built in 1962. But then we forget it was converted to a torture centre only 40 years ago, in the mid 1970’s.

20,000 prisoners at Tuol Sleng were tortured, interrogated and “processed” before transportation to the killing fields, seven survived. Seven survived, out of twenty thousand.

Our guide was Socmail a quietly spoken lady in her mid fifties. As she led our small party into the classrooms converted to torture chambers she recounted how the monks, artists, professionals, doctors, teachers, the educated and intellectuals were all arrested on suspicion of being traitors to the new state. Bizarrely this included anyone with glasses or soft hands and those who could speak a foreign language.

The decaying 15 ft square rooms, had the original rusting beds in place with their chains and shackles attached, alongside the instruments of torture. Every inmate was interrogated each day until they confessed to something, anything to stop the pain.

The rooms would have included a typewriter so when the prisoner admitted to an act of treason the interrogator would stop the punishment and record the confession. Once completed it was given to the victim for an X to be scrawled onto the paper. They had in effect signed their own death warrant, the Khmer Rouge believed they now had the justification to send the prisoner to the killing fields.

My first impression was surprise that this torture centre, or Genocide Museum as it is now known, was right in the middle of the city. It looks like any other high school; five three storey buildings, about the size of a UK junior school, face on to a play area with gym apparatus, courtyard and green lawns. We were to find out later that this play area and apparatus was adapted to torture prisoners.

Surprisingly, it is not in ruins, far from it, it is in near perfect condition having been built in 1962. But then we forget it was converted to a torture centre only 40 years ago, in the mid 1970’s.

20,000 prisoners at Tuol Sleng were tortured, interrogated and “processed” before transportation to the killing fields, seven survived. Seven survived, out of twenty thousand.

Our guide was Socmail a quietly spoken lady in her mid fifties. As she led our small party into the classrooms converted to torture chambers she recounted how the monks, artists, professionals, doctors, teachers, the educated and intellectuals were all arrested on suspicion of being traitors to the new state. Bizarrely this included anyone with glasses or soft hands and those who could speak a foreign language.

The decaying 15 ft square rooms, had the original rusting beds in place with their chains and shackles attached, alongside the instruments of torture. Every inmate was interrogated each day until they confessed to something, anything to stop the pain.

The rooms would have included a typewriter so when the prisoner admitted to an act of treason the interrogator would stop the punishment and record the confession. Once completed it was given to the victim for an X to be scrawled onto the paper. They had in effect signed their own death warrant, the Khmer Rouge believed they now had the justification to send the prisoner to the killing fields.

Unbelievably brutal and barbaric torture at Tuol Sleng included electric shock, water boarding with boiling water, nail extraction with alcohol poured over the wounds, drowning, hanging and scorpion stings for the women. This was torture on an industrial scale, vicious, inhumane and excessively cruel.

The Security of Regulation sign remains in the school courtyard, new inmates were forced to recite it when they arrived.

Unbelievably brutal and barbaric torture at Tuol Sleng included electric shock, water boarding with boiling water, nail extraction with alcohol poured over the wounds, drowning, hanging and scorpion stings for the women. This was torture on an industrial scale, vicious, inhumane and excessively cruel.

The Security of Regulation sign remains in the school courtyard, new inmates were forced to recite it when they arrived.

Each inmate was photographed on arrival and if they died during torture they were photographed again so the image could be sent to the Khmer Rouge officials.

It was during this explanation that Socmail quietly told us that her brother and her father, a teacher, had both been taken to Tuol Sleng, never to return. Our little group fell silent, what can you say?

At the age of 13 she was expelled from Phnom Penh and forced to walk the 183 miles to Bat Tambang to work in the rice fields for the Kampuchea Democratic Regime, it took three months. Socmail said she worked 12 hours a day for three years, eight months and twenty days, that was forty three years ago, she had counted each day there.

We were shown classrooms on the second floor where up to 50 prisoners were shackled together to sleep on the hard stone floors. The rusted rods and manacles were piled in a corner and the steel hooks in the floor were still in place. Greying black and white photos on the walls showed what was found in the torture rooms when Phnom Phen was liberated; 14 tortured bodies bloodied, bare and broken were left on their beds.

Further rooms were lined with thousands of mug shots of prisoners, some alive some dead, all were tortured. Barbed wire was still strung across the exterior landings to prevent suicide, death was a better alternative than life in the prison. The tour was remorseless in its brutal reality.

Each inmate was photographed on arrival and if they died during torture they were photographed again so the image could be sent to the Khmer Rouge officials.

It was during this explanation that Socmail quietly told us that her brother and her father, a teacher, had both been taken to Tuol Sleng, never to return. Our little group fell silent, what can you say?

At the age of 13 she was expelled from Phnom Penh and forced to walk the 183 miles to Bat Tambang to work in the rice fields for the Kampuchea Democratic Regime, it took three months. Socmail said she worked 12 hours a day for three years, eight months and twenty days, that was forty three years ago, she had counted each day there.

We were shown classrooms on the second floor where up to 50 prisoners were shackled together to sleep on the hard stone floors. The rusted rods and manacles were piled in a corner and the steel hooks in the floor were still in place. Greying black and white photos on the walls showed what was found in the torture rooms when Phnom Phen was liberated; 14 tortured bodies bloodied, bare and broken were left on their beds.

Further rooms were lined with thousands of mug shots of prisoners, some alive some dead, all were tortured. Barbed wire was still strung across the exterior landings to prevent suicide, death was a better alternative than life in the prison. The tour was remorseless in its brutal reality.

Of the seven survivors, two are still alive today, one of them is Chum Mey. We visited his cell, number 022, a clumsily built brick space of about six feet in length and no more than three feet wide, his chains, shackles and latrine box remain. He survived gunfights with the Khmer Rouge, rocket attacks during the civil war and having been dragged blindfolded to Tuol Sleng, endured 12 days and nights of repeated beatings, torture and electrocution. He lost his wife and four children during the brutal Khmer Rouge regime and saw friends and family chained, tortured and processed in the assembly line of death.

He confessed to counter revolutionary work for the CIA, an organisation he had never heard of before the torture began, but anything to stop the pain. He was a mechanic by trade and his life was spared when he offered to fix his own interrogators’ typewriter. He was given food and put to work mending all the prison typewriters until the liberation troops arrived.

I asked Socmail about his life after the liberation in 1979.

‘You can ask him yourself,’ she said, ‘he’s visiting today, would you like to meet him?’ This took me completely by surprise, but what an honour, what a rare privilege.

Chum Mey is now a charming, cheerful and contented 86 year old. Perhaps surprisingly, he is happy to talk about his time in Tuol Sleng, maybe it’s part of the healing process, but his physical scars are still apparent.

Of the seven survivors, two are still alive today, one of them is Chum Mey. We visited his cell, number 022, a clumsily built brick space of about six feet in length and no more than three feet wide, his chains, shackles and latrine box remain. He survived gunfights with the Khmer Rouge, rocket attacks during the civil war and having been dragged blindfolded to Tuol Sleng, endured 12 days and nights of repeated beatings, torture and electrocution. He lost his wife and four children during the brutal Khmer Rouge regime and saw friends and family chained, tortured and processed in the assembly line of death.

He confessed to counter revolutionary work for the CIA, an organisation he had never heard of before the torture began, but anything to stop the pain. He was a mechanic by trade and his life was spared when he offered to fix his own interrogators’ typewriter. He was given food and put to work mending all the prison typewriters until the liberation troops arrived.

I asked Socmail about his life after the liberation in 1979.

‘You can ask him yourself,’ she said, ‘he’s visiting today, would you like to meet him?’ This took me completely by surprise, but what an honour, what a rare privilege.

Chum Mey is now a charming, cheerful and contented 86 year old. Perhaps surprisingly, he is happy to talk about his time in Tuol Sleng, maybe it’s part of the healing process, but his physical scars are still apparent.

We met for a few minutes, I have to say I was overwhelmed by this guy. I had just heard his tragic story and stood where he was tortured yet he greeted me like an old friend. The lump in my throat made my voice falter and tears stung my eyes as he took my hand and posed for a photograph, he was far more in control than me. How do you react in such circumstances? Frown, glare, grimace? I turned to him to see a broad smile and genuine happiness on his face. How my wife Helene managed to take the shot with tears streaming down her face I don’t know but that picture and the signed book I have from him are extremely special and treasured souvenirs from our amazing 10 month adventure.

We talked for a few minutes through an interpreter about his time spent 40 years ago in the very place he was now visiting as a guest. He was keen to explain the torture and showed me his broken bent fingers where he tried to defend himself from the clubbing he received all those years ago, and the deformed toes where his nails had been viciously pulled from their sockets with pliers. His body may not have healed but his mind was alert and quick, answering my questions explicitly and with clarity.

‘Why are you here today?’ I asked, ‘surely you would prefer to forget the past and lead your own life without being reminded of the atrocities you experienced?’

‘No, David,’ he was quick to correct me. ‘I am one of a handful to survive and most of them are now gone. I believe it is my duty to tell my story, I want the world to know what really happened. I don’t want those thousands who died horrible deaths to be forgotten. Then perhaps we won’t see this terrible time repeated again, not just here, but anywhere in the world.’

What a courageous man.

While Pol Pot’s utopian vision was becoming a reality his cleansing programme grew to staggering levels. When an interrogation extracted a name, the whole family would be arrested and sent to Tuol Sleng and wiped out at the killing fields. This was our next visit.

Choeung Ek is about 10 miles southeast of the city in the lush landscape of rural Cambodia, it is also the most well known of the 300 killing fields found all over the country. It is here that the inmates from Tuol Sleng were transported in their thousands for execution.

We met for a few minutes, I have to say I was overwhelmed by this guy. I had just heard his tragic story and stood where he was tortured yet he greeted me like an old friend. The lump in my throat made my voice falter and tears stung my eyes as he took my hand and posed for a photograph, he was far more in control than me. How do you react in such circumstances? Frown, glare, grimace? I turned to him to see a broad smile and genuine happiness on his face. How my wife Helene managed to take the shot with tears streaming down her face I don’t know but that picture and the signed book I have from him are extremely special and treasured souvenirs from our amazing 10 month adventure.

We talked for a few minutes through an interpreter about his time spent 40 years ago in the very place he was now visiting as a guest. He was keen to explain the torture and showed me his broken bent fingers where he tried to defend himself from the clubbing he received all those years ago, and the deformed toes where his nails had been viciously pulled from their sockets with pliers. His body may not have healed but his mind was alert and quick, answering my questions explicitly and with clarity.

‘Why are you here today?’ I asked, ‘surely you would prefer to forget the past and lead your own life without being reminded of the atrocities you experienced?’

‘No, David,’ he was quick to correct me. ‘I am one of a handful to survive and most of them are now gone. I believe it is my duty to tell my story, I want the world to know what really happened. I don’t want those thousands who died horrible deaths to be forgotten. Then perhaps we won’t see this terrible time repeated again, not just here, but anywhere in the world.’

What a courageous man.

While Pol Pot’s utopian vision was becoming a reality his cleansing programme grew to staggering levels. When an interrogation extracted a name, the whole family would be arrested and sent to Tuol Sleng and wiped out at the killing fields. This was our next visit.

Choeung Ek is about 10 miles southeast of the city in the lush landscape of rural Cambodia, it is also the most well known of the 300 killing fields found all over the country. It is here that the inmates from Tuol Sleng were transported in their thousands for execution.

Between 1976 and ’78 Tuol Sleng would send up to 300 people a day to Choeung Ek. Tortured, terrified and traumatised victims the Khmer Rouge believed had committed crimes against the state. Trucks loaded with men, women, children and babies to be slaughtered the night they arrived.

The area has hardly been touched since the end of the Khmer Rouge regime in 1979. Although there are paths and some boardwalks over the 129 mass grave pits, when it rains there is still the faint odour of rotting corpses, while bones, teeth and pieces of clothing rise to the surface.

Each visitor is provided with headphones and an audio commentary so the memorial site is eerily quiet as groups and couples split up for each individual to try and understand this astonishingly sad environment at their own pace. There are visitors in silent contemplation sitting under trees, others unashamedly sobbing as the narrative plays out and some clearly unable to take in what they are seeing and hearing. It is tough.

Likewise, Helene and I separated rather than share the experience, I think one has to manage this in one’s own way.

Victims were told they were being taken to a safer environment but were blindfolded and murdered on the side of the mass graves in the most efficient, expedient and inexpensive way possible. Few bullets were used, they were too costly, so they were hacked and bludgeoned to death with what they called “killing tools”, nothing more than farm implements. Scythes, axes, bayonets, cleaning rods, chisels, knives, hammers and clubs were displayed alongside the skulls that they had beaten and broken.

One mass grave of about 15 x 30 feet contained 450 victims, another 166 without heads. The Magic Tree was in the centre of the mass graves, it was used to hang speakers playing loud music during the executions to drown out the screams of the dying. The brutality here was almost palpable.

The most harrowing by far was The Killing Tree alongside a 12 x 12 foot mass grave of 100 naked women, young children and babies. Unbelievably, the bullets were reserved for the babies, not out of any sense of morality, compassion or sympathy but grotesquely for fun. One executioner would throw the baby in the air for another to shoot at it.

The obscenity of the executioner’s actions continued with The Killing Tree, it has a large well established trunk perhaps a metre in its diameter, it is covered with thousands of donated colourful wristbands, beside it is a distressing hand painted sign.

Between 1976 and ’78 Tuol Sleng would send up to 300 people a day to Choeung Ek. Tortured, terrified and traumatised victims the Khmer Rouge believed had committed crimes against the state. Trucks loaded with men, women, children and babies to be slaughtered the night they arrived.

The area has hardly been touched since the end of the Khmer Rouge regime in 1979. Although there are paths and some boardwalks over the 129 mass grave pits, when it rains there is still the faint odour of rotting corpses, while bones, teeth and pieces of clothing rise to the surface.

Each visitor is provided with headphones and an audio commentary so the memorial site is eerily quiet as groups and couples split up for each individual to try and understand this astonishingly sad environment at their own pace. There are visitors in silent contemplation sitting under trees, others unashamedly sobbing as the narrative plays out and some clearly unable to take in what they are seeing and hearing. It is tough.

Likewise, Helene and I separated rather than share the experience, I think one has to manage this in one’s own way.

Victims were told they were being taken to a safer environment but were blindfolded and murdered on the side of the mass graves in the most efficient, expedient and inexpensive way possible. Few bullets were used, they were too costly, so they were hacked and bludgeoned to death with what they called “killing tools”, nothing more than farm implements. Scythes, axes, bayonets, cleaning rods, chisels, knives, hammers and clubs were displayed alongside the skulls that they had beaten and broken.

One mass grave of about 15 x 30 feet contained 450 victims, another 166 without heads. The Magic Tree was in the centre of the mass graves, it was used to hang speakers playing loud music during the executions to drown out the screams of the dying. The brutality here was almost palpable.

The most harrowing by far was The Killing Tree alongside a 12 x 12 foot mass grave of 100 naked women, young children and babies. Unbelievably, the bullets were reserved for the babies, not out of any sense of morality, compassion or sympathy but grotesquely for fun. One executioner would throw the baby in the air for another to shoot at it.

The obscenity of the executioner’s actions continued with The Killing Tree, it has a large well established trunk perhaps a metre in its diameter, it is covered with thousands of donated colourful wristbands, beside it is a distressing hand painted sign.

A 62 metre tall Memorial Stupa was built in 1988. It is a Buddhist construction of 17 shallow levels with acrylic sides, the first ten of which displays 9,000 skulls. The remaining levels carry some of the victim’s bones but there was just not enough space to display them all so most are left in the earth.

A 62 metre tall Memorial Stupa was built in 1988. It is a Buddhist construction of 17 shallow levels with acrylic sides, the first ten of which displays 9,000 skulls. The remaining levels carry some of the victim’s bones but there was just not enough space to display them all so most are left in the earth.

The day’s experience was of course shocking and distressing, I believe we were both somewhat traumatised by what we encountered.

As we left the Killing field of Choeung Ek the audio narrative finished with a poignant message. “What happened here was tragic but not unique. It’s happened across the globe in the past, and may well happen again. It is a lesson we must all learn from, so as you return home remember our past when you look towards your future.”

It was a powerful message, echoing the conversation I had earlier in the day with the brave Chum Mey. In my book of our 10 month adventure I was tempted not to describe what I saw and heard. But my conversation with Chum Mey and the final audio message persuaded me otherwise. Perhaps we too have a duty to tell the story of what really happened, this is why I believe you should visit Phnom Penh prison and the killing fields.

David Moore is Author of ‘Turning Left Around the World’. Published by Mirador and available from Amazon, it is an entertaining account of David and his wife’s travel adventures – often intriguing, frequently funny and occasionally tragic.

If you would like to be a guest blogger on A Luxury Travel Blog in order to raise your profile, please contact us.

The day’s experience was of course shocking and distressing, I believe we were both somewhat traumatised by what we encountered.

As we left the Killing field of Choeung Ek the audio narrative finished with a poignant message. “What happened here was tragic but not unique. It’s happened across the globe in the past, and may well happen again. It is a lesson we must all learn from, so as you return home remember our past when you look towards your future.”

It was a powerful message, echoing the conversation I had earlier in the day with the brave Chum Mey. In my book of our 10 month adventure I was tempted not to describe what I saw and heard. But my conversation with Chum Mey and the final audio message persuaded me otherwise. Perhaps we too have a duty to tell the story of what really happened, this is why I believe you should visit Phnom Penh prison and the killing fields.

David Moore is Author of ‘Turning Left Around the World’. Published by Mirador and available from Amazon, it is an entertaining account of David and his wife’s travel adventures – often intriguing, frequently funny and occasionally tragic.

If you would like to be a guest blogger on A Luxury Travel Blog in order to raise your profile, please contact us.Did you enjoy this article?

Receive similar content direct to your inbox.

David, I agree, you do have a duty to tell that story. It must be told over and over again. Once again the world is becoming a dangerous place as some countries lurch towards extremist governments. We need to be reminded of how barbaric and evil man can be to his feel man.

Great travel writing should have something to say about the world. Even if the message is hard to bear and painful to read the power of the prose should draw the readers in and compel them to read on. This piece is timeless. I hope that people will still be reading David’s book in two, three, maybe even four centuries time.

I can not help but think of that old quote, “History repeats itself, it has to, nobody listens.”

I did this same tour a few years ago, but in reverse, first the fields, then the prison. We were offered an opportunity to speak with one of the survivors. I regret we didn’t take advantage of it. I kept thinking — what do you ask someone who has been through something so horrific?

I can imagine this being an incredibly emotive visit. It’s awfully brutal to think a High School was transformed into such a vicious prison and torture centre, where even the playground had its innocence stolen for such vile uses. I had no idea the number ran so high up to 20,000 prisoners that were interrogated there, only for 7 to survive. That is utterly heartbreaking. Tours like this are so important in keeping history alive, in remembering atrocities so they don’t repeat themselves, in not forgetting those that were so abused and who lost their lives. The mug shots is a good way to pay tribute, while obviously also bringing the reality of the events into stark light.

It’s wonderful you got to meet Chum Mey, and what a timely visit to go when he was also visiting. An incredible, brave man indeed, and it’s heartening that his experiences have made him want to work towards a better world by keeping the story alive and not forgetting those who tragically lost their lives.

This is an incredibly fascinating post, thank you so much for writing it and keeping this important part of history alive.

I suppose it is natural that when we travel, partly to get away from our routine lives, that we tend to head for the idyllic white sand beaches or the world’s galleries with exquisite art. Sadly, there’s another bleaker and darker side to the world. It is important that, as we travel, we recognise how many people have suffered and died at the hands of evil regimes. I believe that it is essential that honest pieces like this post, commemorating the bravery of the few who survived, should continue to be written.

Many thanks for your comments, particularly those supporting the need to tell this story…

There has been a great deal of controversy over the commercialism of the sites we visited.

In fact Schools in Cambodia no longer include the atrocities as part of the curriculum, government influence here perhaps, which sounds to me like trying to rewrite history.

They argue that Cambodia has a very young population due to the barbaric actions of the Pol Pot regime in the mid 1970’s, indeed by 2005 three quarters of Cambodians were simply too young to remember the Khmer Rouge years.

Is that a reason to tear the chapter out of the history books?

It has been said that Cambodia will take 100 years to recover from Pol Pot’s ruthless revolution, and that may be true, but would it be any quicker if the history lesson is ignored?

Thanks for your support and please share this difficult story with your friends and family

Many thanks

David

I think it’s part of getting to know Phnom Penh, morbid as it is, with all those skulls in display. The reality is that their history shaped how they live and value what they have today. I can’t imagine the hardship of those who survived went through. Just reading about it makes me sad and angry at the injustice that’s been done here. Similar to what I feel whenever I read about Auschwitz.

I have a great experience on this place. As you walk through it’s four walls, your audio guide brings the museum’s displays of torture techniques to life.

When my friend and I visited the museum, we were both shocked to the core and deeply moved. A visit to S-21 may not be what immediately springs to mind when you think of Cambodia, but it’s still a must-see on any Phnom Penh itinerary.

As a visitor, we must learn and reflect upon this period during our time exploring Cambodia.